Turning-points

Turning-points ^

A turning-point leads the plot into a new, different and unexpected direction. This can be caused by a decision, a piece of information, an incident or an understanding. It closes one narrative unit and creates a new narrative situation at the same time.

The function of turning-points is to break up linear plot development and to cement the audience’s interest. To make sure that a story doesn’t become predictable it is important that it doesn’t move forward and end in a direct and straight forward way but that it moves along circuitously toward its resolution.

Each turn sets up a new question which needs to be answered by the following development: What are their effects on the subsequent progress of the film?

The time period between the set up of a question and its resolution depends on the change. While the dramatic arc of a small change my span over just one scene, the resolution of the central question lasts until the end of second act.

Major turning-points ^

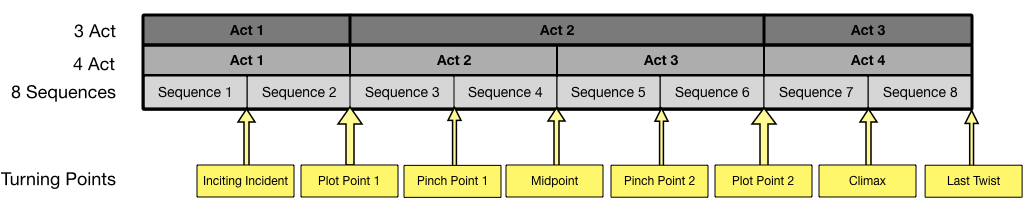

A storyline has up to eight central turning points. These points redirect the plot in such a powerful way that it changes its course: a positive development becomes negative and a negative development turns positive. The most extreme form of a turning point is called a reversal.

The major turning-points are clearly defined and structurally fixed: inciting incident, plot point 1, pinch point 1, midpoint, pinch point 2, plot point 2, climax and last twist. The two plot points divide the three acts. Therefore they always cause a major change within the plot. Midpoint and climax, on the other hand, do not necessarily need to set off a major change. They merely offer the chance for a change/turn. This means that a story depending on its individual development passes through two to four major turns. The breakdown of the plot through the use of the key turning-points produces different structural styles of a film story.

Each storyline contains its own turning-points. The A-storyline’s turning point defines the structure of the entire plot. The other storylines’ turning-points connect the different story strands. This way the turning-point of one storyline has an effect on another storyline. The turning-point of a secondary storyline can cause a change/turn within the main storyline. The turning-points of various storylines are clustered even without direct links to create a structural and dramatic unity of the story. Yet by placing them slightly apart they are linked without having their transitions blurred.

Micro turning-points ^

Besides the major turning points a story also possesses a number of micro-turning-points representing merely gradual change. In principle it is possible and desirable to end each sequence, scene, situation and action with a change and therewith carry over into the next part of the film. The number of micro-turning-points is variable and their position is flexible.

Internal and external change point ^

Generally a turn is composed of two parts: a break of an internal action (internal change point) and consequential new focus of the external course of action (external change point). A change, a revelation or disclosure may, for example, cause the main character to change their plan.

Inciting Incident ^

The inciting incident (also called: inciting event, hook, call to adventure, point of attack, catalyst) gets the action rolling and sets up the first plot point. It is linked to the first plot point by showing its negative and positive prefix and thereby dividing the first act into two halves. The protagonist receives her impulse through the inciting incident. Here she is forced to deal with a specific task. She is dragged out of her habitual day to day life and pushed into alert.

Plot Point 1 ^

The plot point 1 (also called: break into act II, first revelation, point of no return) separates the first from the second act. It leads the plot into an ascending positive or into a descending negative development. Ideally it embodies the best or worst case scenario for the protagonist depending on his exposition. By doing this the plot point 1 sets up the central question of the film which will affect the entire second act.

Pinch Point 1 ^

The first pinch point occurs after the first quarter of the second act – i.e. after approx. 3/8 of the story. It provides the protagonist with new clues and reveals the main conflict of the story. At the same time it serves as a reminder of the antagonist’s power by making the protagonist feel the “pinch” of the antagonistic force. Thus it sets up the next 1/8th of the story.

Midpoint ^

As its name points out the midpoint is in the middle of the second act and divides the entire story into two halves. It offers a possible turning-point. This means that at this point of the story a change/turn may occur but doesn’t have to. It is also possible that the positive ascending or the negative descending development progresses until the plot point 2.

Pinch Point 2 ^

The second pinch point mirrors the first pinch-scene – in its content as well as structure. It takes place after the third quarter of the second act – after approx. 5/8 of the story – and recalls the central conflict once again. At the same time, the second “pinch” foreshadows the confrontations that are yet to come, reminding both the protagonist and the audience what is at stake. Together the two pinch scenes act as the film’s structural ‘pliers’.

Plot Point 2 ^

Just like the plot point 1 the plot point 2 (also called: break into act III, third revelation) represents an obligatory turning-point of the overall story. It separates the second from the third act and constitutes the end of the central tension. It delivers the (preliminary) solution to the central question set up by the plot point 1.

Climax ^

The final tension of the film culminates in the climax (also called: showdown, battle, resolution). It divides the third act into two halves. The climax may confirm or reverse the result of the second plot point. Therefore the climax is a moment when the plot is ultimately determined.

Unlike the other turning-points the climax is not only structurally defined. As the moment of highest tension in the film it also contains a substantial dimension: it is the result of the showdown in which the protagonist is tested existentially.

Here the protagonist has to prove what she’s learned: it is the ultimate chokepoint she has to pass to achieve her ‘want’. The climax is the funnel where all characters and storylines are brought together. Here is where all energies are clustered, where all incompatible objectives, interests and values of the conflicting parties clash. Everything that has been planted during the entire film is now paid off. The protagonist is challenged in her very own nature, mind and body at the same time. Her consciousness and perception are heightened. The audience’s attention is increased through the use of suspense by withholding information from the protagonist.

Being confronted with his own mortality and fragility the protagonist feels the meaning and value of life. He has to employ his sharpened senses as well as his newly accumulated knowledge of himself and the world. Now all his previous understanding and experience have to prove themselves in the real world. At this point the protagonist and antagonist are most alike and yet this conflict of values exposes their crucial difference. The film’s theme and its truth are promptly revealed to the audience. Now the story grows beyond its narrative – i.e. temporal, spatial and individual – limitations and offers universal connections.

When it is said that the end of a movie is the most crucial element what is really meant is the climax. It is the concentric point of the film – this is where everything radiates from: forwards and backwards. The climax passes over to the catharsis of the protagonist and the audience.

An ‘anti-climax’ occurs when the expectations regarding the climax are not met and the climax simply doesn’t happen.

Last Twist ^

Instead of the apparent ending of the story there may be a completely unexpected turn of events right at the very end, often in the last scene or in the very last shots: the last twist.

A prime example of a last twist is that the supposedly dead monster is not dead…

Reversal ^

When at the end of act two resp. in act three the events start culminating towards a resolution turning-points become reversals. That’s how the plot can suddenly reverse into its opposite at the plot point 2, the climax or the last twist so that the protagonist is on an emotional roller coaster. Aristotle called this extreme case of a turning-point a peripetia.

Field, Syd: Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. 2005.

Comments are closed.