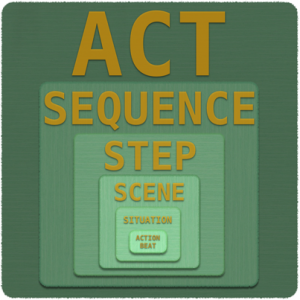

Narrative units

The narrative units constitute the skeleton of a film. Not only do they carry the narrative arc of the entire film, but also its micro narrative strands. The same narrative principles apply to a scene as well as to the entire film.

Act ^

At its most basic level, a closed story structure film is made up of three acts. These structure the film into beginning, middle and end – i.e. an exposition, a development and a resolution. The second act is twice as long as the first and third act. The acts are separated by plot points and are further divided into half-acts by the inciting incident, the midpoint and the climax.

But not only the macro-structure is divided into acts: storylines, scenes and even situations can be broken down into acts.

Step ^

A step is a move forward within the plot (action step) or a structure unit that fulfills a specific narrative function (story step). As part of the development process a story or storyline is divided into steps. Every step responds to the question of what will happen next.

Therefore a step represents one period of a film, it can be an episode, a sequence or scene. Often also the scene-selection options on a DVD are sub-categorized in steps.

Sequence ^

A sequence ties together thematically connected scenes spanning one dramatic arc. They may focus on one incident, a time span, a character or a relationship between characters.

Scene ^

As a continuous plot unit a scene follows the units of time and action. A scene takes place at one location without any temporal interruption. It may be made up of a closed dramatic arc with a structure and turning points matching the macro-structure or it may represent a ‘bit’ – a short information unit. Through the use of momentum scenes are dynamically linked.

A scene is composed of situations which are again composed of actions. Each scene has its own protagonist in pursuit of a specific want. This central character of a scene doesn’t necessarily have to be the main character of the film. While an outline designs each scene it is written out in full in a script. This process is called dramatic writing.

There are several scene categories:

- Function scenes provide information or serve the overall understanding of the plot. They derive their meaning from their context.

- Atmosphere scenes are generally free from functional obligations and have an autonomous expression value. They diversify and intensify the story on a thematic level without driving the plot forward or give you a “feel good” moment.

- Counterpart scenes mirror other scenes and usually belong to a different storyline.

- Decision scenes are action-focused scenes – their outcome determines the further development of the story.

- Set-up scenes create the premise for subsequent major plot elements, e.g. an incident, a decision, a turning point, a revelation or recognition.

- After-effect / Aftermath scenes go after decision scenes. They provide the audience with space and time to (emotionally) ‘digest’ what happened or to create release after a period of tension. Like atmospheric scenes they primarily communicate a feeling and mood.

- Master Scenes are the big scenes of a movie that usually go hand in hand with a major turning point in the movie.

- Pinch scenes appear at two points within a story. After the first quarter of the second act – i.e. after approx. 3/8 of the film – the first pinch scene provides the protagonist with new clues and reveals the main conflict of the story. At the same time it serves as a reminder of the antagonist’s power by making the protagonist feel the “pinch” of the antagonistic force. Thus it sets up the next 1/8th of the story.

The second pinch scene mirrors the first pinch-scene – in its content as well as structure. It takes place after the third quarter of the second act – after approx. 5/8 of the film – and recalls the central conflict once again. At the same time, the second “pinch” foreshadows the confrontations that are yet to come, reminding both the protagonist and the audience what is at stake. Together the two pinch scenes act as the film’s structural ‘pliers’. - Transition scenes are bits bridging two scenes.

- The Obligatory scene is the scene the audience has to have to satisfy their need. Usually they are part of the climax – the protagonist and antagonist meet to decide their conflict with each other. The obligatory scene is thus a revelation scene in which the full extent of evil is shown: The evil in the antagonist reveals itself, his mask falls.

Beat ^

The meaning of the term ‘beat’ is very broad. Basically, a beat is the smallest unit of the plot. So a beat can be a step, a sequence or a scene. A scene can also have several beats, especially if it’s a key scene with turning-points.

In addition, the term ‘beat’ also became common for actions that have a strong emotional impact – negative or positive – on a character. As a negative a beat represents an emotional punch in the face of the character. As a positive a beat makes the character’s heart beat faster.

A beat has the strongest effect when it strikes a character’s (positive as well as negative) nerve because this is where she’s the most vulnerable and sensitive: here she suffers the most, here she’s the happiest when praised or even loved in spite of or even because of her weakness.

In any case a beat creates dynamic relationships between characters and results in a change of status between the character sending and the character receiving the beat. The status of a character receiving a negative beat declines while the status of the sender rises. A character receiving a positive beat rises within the overall structure of character relationships.

Situation ^

Each turning point establishes a new narrative situation. Turning points within a scene further divide a scene into several situations. With each new situation the status and/or attitude of the characters involved changes. Turning points cause a polarity / status shift between the characters: the positive attitude of one character turns into a negative one while the negative attitude of the other character becomes positive. The high status of one character is lowered while at the same time the character of previously lower status rises within their hierarchy. The scene tilts over. This is the way in which character relationships as well as scene leads change: a previously dominant character turns passive after a negative beat and another character takes over. Scenes thrive on having character changes – they enter and leave a scene in a different state. Ideally there is a big discrepancy between the first and final situation of a scene. Each situation is then further divided into several actions:

Action ^

An Action is the smallest dramatic unit of a story and is directly linked to a character. It describes a single and precise action. An activity – in contrast – merely describes a general undertaking, a movement or an engagement. An action is relevant for the plot. Every action that is aimed at another character causes a reaction and therewith a new action. An interaction constantly generates new actions in a ping-pong-style. An action which has an (emotional) effect on a targeted character is called a beat.

Further Reading

- Field, Syd: Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. 2005.

- McKee, Robert: Story: Substance, Structure, Style and The Principles of Screenwriting. New York 1997.

Comments are closed.