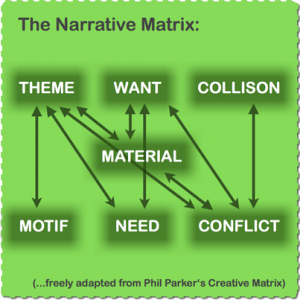

Narrative categories

The story material is the distinctively – temporally, spatially and culturally – fixed matter of a story. The material may deal with a social problem, may use a historic event as blue print, may be based on a piece of literature or may outline a fictional catastrophic scenario. The material is not to be confused with the theme of a story:

As the story material’s counter thought the theme is the abstract fundamental idea of a story. It points out the exemplary element of a story and is the most common denominator that a film can be reduced to. While there is countless story material, there are only a limited number of themes.

A film only becomes memorably by raising a theme while making sure to focus on just one not several themes. One important prerequisite for the perceived coherency of a film is its thematic unity.

The theme of a film expresses a human value or anti-value. Examples for values are: tolerance, dignity, self-discovery, friendship, love, loyalty/solidarity, trust, respect, happiness, meaning, freedom, justice, belief, honesty, loneliness. Examples for anti-values are: inhumanity, greed, hatred, exclusion, betrayal, disloyalty, selfishness.

To explore the theme on a deeper level one can express it through dualism. It is possible to juxtapose a positive and negative value. A theme becomes ambivalent and complex by letting two positive values compete – e.g. ‘friendship vs. love’ (‘When Harry met Sally’, 1989).

This thematic conflict is based on the universal contrast and refers to the need. It is not to be confused with the plot’s conflict which names the specific polarity and refers to the want. What the audience perceives as the theme is the protagonist’s ‘need’ – what the story is ‘really’ about.

Because of its dual tension the theme constitutes a driving force for the creative writing process: it is the controversial issue to be proven. Like in a discourse an alternate argument for each side runs through the film: the thesis and antithesis are alternately discussed while the story has to do justice to both. The writer (as well as his protagonist) undergoes a ‘war of ideas’ process to finally arrive at and make a specific / personal – statement which is revealed in the climax. It becomes clear how the writer sees the world and what he has to tell the audience. Dramatically speaking: The film’s truth and ‘message’ emerge.

The theme penetrates the entire film on all levels in all single storylines (thematic patterning). This way it creates several levels of meaning reaching into the smallest dramatic unit and bestows the film with focus and depth. It runs like a common thread through the film in form of motifs. But the theme should also be included in the logline, the premise, the central question, the tagline as well as the title.

A motif is a symbolic association shaping the film thematically and/or cohering it and referring to the ‘message’ of the film. It may be visual or auditory, i.e. consist of a certain image, gesture, sound, succession of sounds or words. The theme ‘mortality’ in a film, for example, may be represented by an ‘hourglass’, a ‘withered flower’, a ‘soap bubble’, a ‘ruin’, a ‘dying candle’ etc.

The film ‘Cherry Blossoms – Hanami’ by Doris Dörrie (2007) has the reoccurring motifs ‘birds’ (as symbol for freedom), ‘shadows’ (as metaphor for memory, past and death), ‘neatly arranged shoes’ (as expression of a need for order) as well as a ‘tied handkerchief’ (as sign of disorientation).

A film may have several reoccurring motifs. Motifs often transform in the process and therewith comment on the development of the story/character. The defining motif of a film is called leitmotif.

Motifs are mainly woven into the story during the dramatic writing process. They’re perceived on a sub- or half-conscious level. By varying the reappearance of a reoccurring motif one creates a tight motif-blanket for the surface plot in which the theme is manifested (thematic patterning). Motifs are used to mirror, enlarge and internalize the theme.

In the open story structure reoccurring motifs are very important. They sometimes connect / structure the story stronger than the external plot and therewith act as subtle ‘road maps’.

The dramatic conflict (also called: obstacle, blocker) derives from the want: On his journey the protagonist is confronted with big obstacles and issues usually in the form of antagonistic powers because his interests come up against someone’s counter-interests. The resulting conflict is based on different ways of life or moral concepts, on greed or a deficit: the lack of understanding, health, morals, time, money etc. The conflicting parties fight with each other. Their goals are mutually exclusive. A one-sided solution is imperative as a compromise is impossible. The conflict triggers inevitable decisions; but to become the central driving force of the plot, it needs a collision as without it the conflict remains static.

There are four levels of conflict: global, situational, interpersonal or intrapersonal:

- The opposing force of the global conflict is a system or a natural power. A system could be a social or political system: two world(view)s collide.

- The counter force of the situational conflict is a specific situation like, for example, time pressure, an impassable obstacle or a severe storm.

- The opposing force of an interpersonal conflict is the antagonist.

- The counter force of the intrapersonal conflict is the protagonist herself: She stands in her own light. This inner conflict often derives from the voice of passion and the voice of reason.

One doesn’t have to choose just one conflict.

On the contrary – the more conflict levels a film has the more complex it is.

Beside the dramatic conflict each story should also contain a thematic conflict originating from the theme’s dualism.

In addition to its conflict the opponents need a shared interest. Only then can a conflict be intensified enough to be translated into a plot so that the conflicting parties collide. Quite often they compete for the same want. Their double motivation makes the protagonist and antagonist dependent on each other, force them to deal with the other character as they cannot avoid each other.

An alternative to shared interests is creating a situation where both conflicting parties are unable to dodge each other. The ‘glue’ that holds the characters together against their will may be, for example, the constraint to live together as a family, to work as colleagues, to live next door to each other as neighbours or to be imprisoned in the same cell. Here a collision is only a matter of time. To balance the conflict both opposing powers – the dividing and the connecting power – should be of equal weight.

The want (also called: goal, desire, intention) is the protagonist‘s mail goal. It represents the external focus of the plot by defining its direction. It affects that which is characteristic of the plot, its distinctiveness, that which makes the story original, special and unique. It is physical, ostensible and specific: the promotion, the victorious contest, or the dream-car. This want doesn’t have to be morally good or right. Often it is the opposite and therewith an expression of infatuation. It is what the character craves or thinks she craves: her professed desire, what she would give anything for. If you asked the character what her goal is, she would have a clear answer. Just as the audience would point out the ‘want’ when asked what the film is about. But in reality it is only a means of the ‘need’.

In the overall structure of the story the first act shows the birth of the ‘want’, the second act the protagonist’s pursuit of the ‘want’ while the third act demonstrates the achievement or failure of the ‘want’. It is possible for the ‘want’ to transform, be divided into stages or develop further.

The need is the universal, archetypical aspect of a story representing the theme of the film. It is revealed by the protagonist pursuing his ‘want’. It is the inner deficit of a character, one she’s not even aware of (yet). Something essential is missing in her life: it’s not something her body is missing, but her soul; something unsubstantial or something that cannot be physically measured. It is a lack of love, dignity, recognition, trust, friendship, independence, attention. This deficit is fundamental. It has existed for a long time; it has been there before the beginning of the film, maybe it has something to do with the character’s wound. It shapes the character. Even when it is ignored, hidden or surpressed, it is still deeply burried within. From this denial derives a quiet longing. This inner need represents the inner drive of the character, her real motivation, but also the reasons for her failure. Her unconscious, need-driven action doesn’t just make her the victim of circumstances, but also the contravener: because of her own yet unrealized mental problems she hurts other people. That is why the ‘need’ makes characters three-dimensional and human.

Only by fulfilling her need can a character find her inner peace.

Comments are closed.