Formal script standards

Hollywood developed a ‘script-grammar’, that intends to make the reception of a script as clear as possible:

The US-American standard requires a 12pts Courier single-spaced font. The historical background is that Courier was the standard typewriter font. Therefore the advantage is that Courier is a mono-space-font with a non-proportional typeface whereby ten characters constitute a horizontal inch and six lines a vertical inch. Since every letter takes up the exact same amount of space its use enables the exact estimate of a script’s length by its page number. When a script is formatted according to these standards one page of script equals about one minute of film. But this, of course, is only a general reference point. In practice pages with less dialogue need more than a minute while pages with lots of dialogue need less.

Another formal standard originating from the time when scripts were written with typewriters is that only those formatting features available to typewriters are used. Therefore the entire script text follows a left-bound layout. Accentuations are limited to capital letters and underlining and exclude italics as well as bold, coloured and highlighted font. Furthermore it applies to all script elements that no hyphenation is used and that all words are spelt out in full – including numbers and times; exceptions are multi-digit numbers, e.g. years.

A (master) scene heading encompasses location and day time details:

- INTERNAL and EXTERNAL refer to the position of the camera.

- Day time information refers to ‘visible’ time. Options are DAY, NIGHT or DUSK; DAWN. Furthermore the writer has the option to specify time details when necessary, e.g. when a flashback is used.

- Location details are usually made up of two parts: the general and the specific setting: When the second part specifies the first they are linked by a slash (/), e.g. APARTMENT / BED ROOM. When both locations are of different character the specific location is listed first followed by the general location. They are separated by a dash (–), e.g. CAR – RURAL ROAD.

- At a certain stage of script development, it is customary and practical to number the scene headings consecutively.

Besides the (master) scene headings (primary sluglines) there are also secondary headings according to the Anglo-American standard. These divide (longer) scenes into situations and cover specific frames. Their practical benefit is to have smaller units and to get a concrete grasp on locations. This enables creating emphasis, clarifying changes in point of view and to stress inserts. Instead of demarcating and organizing sluglines create a flow and to encourage a dynamic production. The use of a mobile camera, along with fluent setting transitions with single locations joint together, is also more suitable to this organic system than a unitary division into Scenes.

For particular montage techniques there are specific scene headings / secondary headings. Their end is explicitly marked, e.g. END OF MONTAGE.

The plot of the screenplay is described in the Action text: This encompasses all actions performed by the characters within the scene, including their movements, gestures, facial expressions, and any interactions with other characters or objects. These descriptions are dynamic and directly relate to the actions that will be seen on screen. They often lead into or supplement dialogues by conveying the emotional or physical state of a character, expressed through their actions. The action elements are crucial for advancing the story and developing the characters.

In contrast, the General text describes the scenery, environment, setting, or atmosphere where the film’s action unfolds. It can include information about the time of day, weather, interior design of a room, or general background details important for contextualizing and audio-visually presenting a scene. The purpose of such general descriptions is to provide a clear picture of where and under what circumstances the scene takes place.

To accentuate specific action elements they are written in ALL CAPS:

- Characters appearing for the first time (also used in treatments)

- Off-scene sounds

- The act of hearing

- Plot relevant objects that suddenly appear

- Scene transitions

- shooting specific details, e.g. camera position (if these are included in the script)

At some points it is acceptable not to write out the entire action or dialogue, but to leave their exact execution to the actors. In this case the note (AD LIB) is used – Latin ad libitum meaning ‘as desired’ – to let the actor know that she can act and speak at her own discretion within the context of the scene.

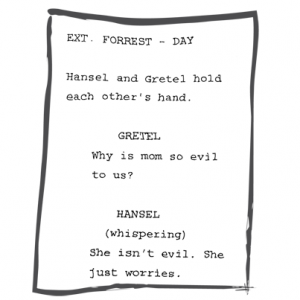

- Each dialogue is formatted as an indented block, separated from the rest of the text or other pieces of dialogue by a free line above and below.

- The name of the character speaking is centred in ALL CAPS.

- When the character speaking is in the scene, but out of view, the affix (O.S.) for off screen or (O.C.) for off camera appears after her name.

- A narrative voice commenting on the action is called a voice over and the affix (V.O.) appears after her name.

- Directly under her name appear the character instructions in the parenthetical (round brackets)

- The dialogue sentences are indented on both sides and are not put into quotation marks. One should try to avoid hyphenation.

- When a dialogue is continued on the next page the affix (MORE) is added at the bottom of the page as well as (CONT’D) (abbreviated) at the top of the next page.

- When a character continues his dialogue without a break but some action instructions need to be inserted the affix (CONT’D) (abbreviated) is placed after the character’s name above the second part of the dialogue (in round brackets).

- When dialogue sentences are to be accentuated in a certain way, the accentuated words are underlined. (This option should only be used to prevent wrong dialogue interpretation – not to predetermine the intonation of the dialogue; don’t tell actors how to do their job.)

- When a character doesn’t finish his sentence an ellipsis (…) is used.

- When a dialogue is interrupted by an external action it is marked with two dashes (—).

- The addition (INTER) (for INTERRUPTING) is used after the character’s name to indicate that he’s interrupting another character.

- When a character speaks with a certain dialect or accent it is possible to write out her dialogue accordingly. This should happen in a subtle way to keep the dialogue readable and also not to tell the actors how pronounce their lines.

- Filling and babbling sound should not be included in the dialogue as these are part of the actors’ dialogue interpretation.

- Lyrics and poems are integrated into the block of dialogue so that a new verse doesn’t start a new paragraph but is instead marked by a slash (/).

- Text messages as well as internet chats are also formatted as dialogue. They are preceded by ON THE DISPLAY / SCREEN which appears instead of the character name. The text is put in quotation marks.

Parentheticals (also Character instructions or Directions) are precise insertions in parentheses within a character’s dialogue. They’re used to indicate aspects which are not evident from the context. They should be used sparingly and not interfere with the production or work of the actors.

Parentheticals are not full sentences but merely a few words not exceeding two lines. Longer parentheticals should go into the general text.

The abbreviation “re” (“regarding”) is used in parentheticals to make it clear that a statement or reaction is related to a specific thing or character, e.g. (re door lock). This helps to make the focus of the action or the character’s attention clearer without using extensive descriptions.

Parentheticals might refer to:

- irony, e.g. (ironical)

- moods, e.g. (tired)

- activities of the speaking character during the dialogue, e.g. (waiting)

- addressees of the dialogue, e.g. (addressing the porter) or (to himself)

- the object or person to which/whom the dialogue is referring, e.g. (re: her new dress) / Do you like it?

- overlapping or interruption of dialogue, e.g. (overlapping) / (interrupting)

- a pause in dialogue: (Pause)

- another language, e.g. (French)

- medial communication, e.g. (over phone / filtered)

A special transition between two scenes may be included in the script. The type of cut is indented and placed at the end of the scene, like CUT TO:.

Examples of distinctive scene transitions are the pointed kick, an ellipse or a cliff-hanger. Contrasting scene transitions are created through the use of e.g. smash cuts or jump cuts. Other special editing types are fade in, fade out, cross- or dip to colour dissolve, match cut or cross cut.

“PRE LAP” literally means “preceding overlap”.

The term describes a technique where the sound from the next scene begins shortly before the visual transition, anticipating the audio of the following scene. While the current scene is still visible on screen, the audience can already hear dialogue, a sound effect, or music from the next scene. In this way, the audio overlaps the visual cut.

A PRE LAP is used as a stylistic device to create a smooth or creative connection between two scenes, making the transition more seamless or dynamic. It gives the viewer a sense of continuity and can enhance suspense, anticipation, or emotional intensity.

The following script combinations are to be understood as inseparable unities and are therefore not to be divided over a page break:

- Scene headings and general text

- Speaking characters, parentheticals and dialogue

- Scene transitions and preceding scenes: When a scene transition does not fit on to a page anymore it should be placed on the next page together with the last sentence of the preceding scene.

When a sentence does not fit on to a page anymore the whole sentence should be put on the next page. Nevertheless – when the relocation of a section creates a gap of more than one third of a page the section needs to be broken up. When a scene is continued on the next page the affix CONTINUED is used.

Further Reading

- Cole, Hillis R. / Haag, Judith H.: The Complete Guide to Standard Script Formats, Part 1. 1980.

- Riley, Christopher: The Hollywood Standard: The Complete and Authoritative Guide to Script Format and Style. 2009.

Comments are closed.