Dramatic writing

First of all, the principle of dramatic writing is that you get into a scene as late as possible and get out of the scene as early as possible. In addition, every scene should “belong” to one character. This means that the scene is written from the perspective of this particular character. It may or may not be the main character.

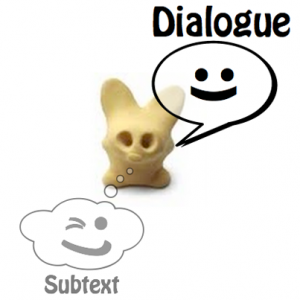

Dialogue

Dialogue should always focus on character exposition rather than to provide information. As a characterising tool it can deliver distance or irony, create a save space, express insecurity, trust or belonging (to a class or region). A character may exaggerate or downplay things in her dialogue – both will give some indication about her character and her present state.

In reality a conversation is very rarely direct. Dialogues appear authentic when for example its answers are ambiguous or only answer a part of the question; when thoughts are wondering mid-sentence; when a character answers a question with another question; when two or three exchanges go past before an earlier question is addressed; when two characters decide a conflict, interrupt each other or when they speak indirectly or via another present character.

Subtext

Subtext is the unspoken meaning, the second level of a scene. It doesn’t just refer to the dialogue, but to the all actions, body language, glances, gestures or tone of voice at every moment of the film. It encompasses everything that stays under the surface. Examples of dialogue subtext are irony and lies, but also covering up, concealing, obscuring or downplaying information. Subtexts that refer to the entire plot are, for example, impatience, antipathy or eroticism.

Scenes live off the proportion between the outspoken and the unspoken. It is the gap that provides them with an inner dynamic as nothing is what it seems.

Subtext is created through the audience’s interpretation of the dialogue or plot. To understand the subtext the audience needs to be privy to what it refers to.

A character can deliberately and knowingly communicate subtext. In this case it’s the writer’s choice how to set the proportion between dialogue and subtext: little subtext makes the scene direct while a lot of subtext can make it subtle and meaningful. A good way to bring subtext into effect is to employ quietness and silence.

But subtext can also be unknowingly expressed, because what people say often doesn’t match what they think or feel. Dialogue and subtext may deviate only slightly, may represent the complete opposite or refer to two absolutely different things that have nothing to do with each other. And still – what is said will reveal what is going on in the mind of a person, what she’s dealing with, what she’s interested in, what’s troubling her. Freudian slips, for example, unmask the thoughts and the unconscious of a person. But also the images and associations used by a person reveal something about their hidden longings, fears and preferences.

Subtext demands a subconscious perception from the audience so that they can grasp the emotional content of a scene. In treatments the subtext is often still spelt out. It is only in the script development that the subtext is translated into a plot. During the rehearsal process the subtext is revealed again as well as verbalised to make the actors aware of it.

Blocking

Blocking is the scenic positioning of actors/characters in relationship to each other on location. It encompasses their location-glance-behaviour, touching and posture. The rough-blocking is part of the scenic description in the script while the fine-blocking is done during the actual shooting.

[…] Can refer to How do you write a dramatic writing? […]